Story-Telling: Why? And why don't the English?

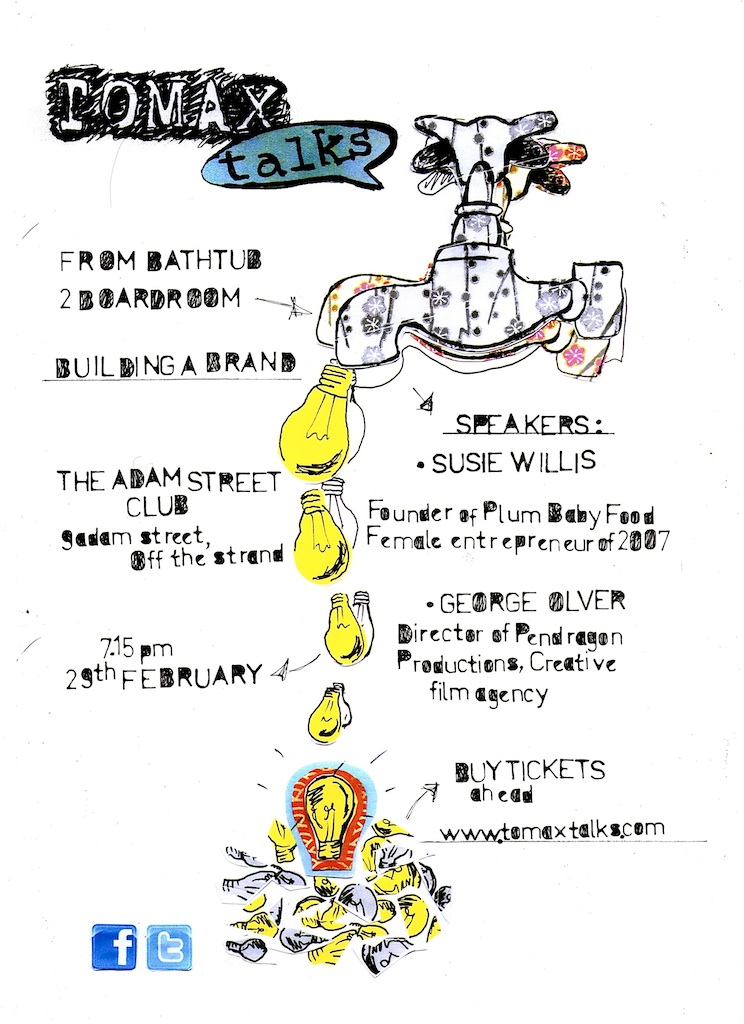

ToMax is running a storytelling competition. It's simple and open to everyone: make a three minute video of yourself or someone you know telling a corking story. You know, the best from the arsenal. Then send it to us. We'll publish the best ten videos on facebook and put the matter to a vote. The winner gets a cash prize and a ToMax membership which gives you and a friend a year of free talks. You only need to look at our calendar for the next two months to see what a gift this is.

Story-telling, it struck me, and language itself, exists in a different space to the one in which it developed. I don't mean to handcuff how language evolved to what it is able to do. But I do want to point out that words didn't use to be recorded. Now, we record them.

Story-telling, it struck me, and language itself, exists in a different space to the one in which it developed. I don't mean to handcuff how language evolved to what it is able to do. But I do want to point out that words didn't use to be recorded. Now, we record them.

In the past, spoken thought was recorded only in the memory of an audience. The words evaporated, leaving only their memory and sense. Story-tellers held their audience captive; they embellished and imparted. The casing of the story dropped away and if the story was passed on, then it was not verbatim. The Gospels relate Jesus' parables. But they don't pretend to be word for word. They get the message across.

Sound recorders are relatively new. Writing is not that new, but a culture of capturing spoken language in written words is. From a young age, we are encouraged to record what teachers tell us in class – on the whole, school children are given blank books and at some point or other expected to copy down words, setting them in stone. It is becoming a popular view on education that the inherited educational apparatus makes unjustified assumptions about how people learn and what good learning is. Ken Robinson, for example, argues in a much-watched TED talk that grouping children into years is an anachronistic hindrance to learning, a hangover from the Victorian era when workhouse education grouped children to reflect the requirements of physical work. You might take this further and say 'written work only assesses one kind of intelligence'. Whether or not you buy into this line of argument, students are largely assessed on the basis of things they write down– exams, coursework. More broadly, people trust text: 'I read it in the paper, it must be true'. All over the shop, recorded thought is valued.

We write down what a single person has said because we think that their message is transportable. Maybe that is linked with the scientific way of thinking which emerged at the start of the 20th Century. People thought that physics would give a thorough explanation of the world, and this same common sense ethos was taken up by philosophers of language. Frege and Bertrand Russell thought that, roughly, the words in our language represented bits of the outside world. So, just as when an artist paints a picture of the world it can be transported away from the artist but still remains the same picture of the same thing, so, I suppose, people got to think that a sentence had the same quality. Pick it up and move it.

We write down what a single person has said because we think that their message is transportable. Maybe that is linked with the scientific way of thinking which emerged at the start of the 20th Century. People thought that physics would give a thorough explanation of the world, and this same common sense ethos was taken up by philosophers of language. Frege and Bertrand Russell thought that, roughly, the words in our language represented bits of the outside world. So, just as when an artist paints a picture of the world it can be transported away from the artist but still remains the same picture of the same thing, so, I suppose, people got to think that a sentence had the same quality. Pick it up and move it.

Well, the question of how words carry meaning is a whole can of worms. But perhaps it is this view of language which means that storytelling has faded. People think 'record it, suck it dry later'. It is fair to say that many stories cannot be picked up and moved. They need to be told. And they are woven together with the speaker, with the expression, the delivery and experience. That is why you need to come to ToMax, and why the footage is an impoverished cousin of the live event.

Perhaps this is all rather obvious. In Britain, we aren't enamoured with stories. But narrative is really important. Every explanation is a narrative; as the author Joe Craig put it at our 'Inspiring Young Minds' evening, every event has many causes and only a story can thread them all together.

And then we need stories as positive myths. Oscar Wilde put his finger on the importance of stories in his essay The Decay of Lying, in which the character Vivien announces: 'One of the chief causes that can be assigned for the curiously commonplace character of most of the literature of our age is undoubtedly the decay of Lying as an art, a science, and a social pleasure'. This is not lying in today's straightforward sense of telling falsehoods. It is lying in the sense of creating fiction. For fiction is not falsehood, although bad fiction undoubtedly is ('Socialist Realist' Art in the Soviet Union was an example of bad fiction. It depicted a bright socialist future as around the corner, as the logical extrapolation of the present state of affairs. But anyone alive at the time could see the gulf between the grim present and the justice of these Socialist Realist utopias). A fiction is a picture of the world which resists the most obvious terms of description, and – perhaps - the simplest explanation.

We need fictions and imaginings to take us beyond our humdrum surroundings, or to brighten them – read a bit of Flann O'Brien to see the laughter and meaning which his absurd stories bring to their rough Dublin setting. Or James Joyce. Our hopes and aspirations, the narratives we have of our own friends – these are healthy fictions. Perhaps we even need fiction to reconcile ourselves with the alluring, but depressing scientific view of the world as determined matter. Unlike some, Kant saw the pre-determination of the universe as irreconcilable with free human choice in the meaningful sense – the sense in which we need it in order to be meaningfully moral. Lots of good stories have choices at their centre. So, all profound reasons to visit ToMax for a yarn or two.

We have been wondering why the English don't tell stories as much as other nations. Get yourself to South Africa, and you will find families huddling around candle-lit tables listening to ripping yarns. In Irish pubs, there are people nursing pints and talking about lepricorns. In England, the same pubs show back-to-back football matches from the Italian third division. In those same Italian towns people are gathering on the veranda with a bottle of wine to hear shaggy dog stories. It seems that in England we don't have much concentration span. In fact, we just don't like people who talk for too long. And I don't mean we have a low tolerance for bores, rather for any speech exceeding a couple of sentences. We just nod and smile and go back to reading the paper.

We have been wondering why the English don't tell stories as much as other nations. Get yourself to South Africa, and you will find families huddling around candle-lit tables listening to ripping yarns. In Irish pubs, there are people nursing pints and talking about lepricorns. In England, the same pubs show back-to-back football matches from the Italian third division. In those same Italian towns people are gathering on the veranda with a bottle of wine to hear shaggy dog stories. It seems that in England we don't have much concentration span. In fact, we just don't like people who talk for too long. And I don't mean we have a low tolerance for bores, rather for any speech exceeding a couple of sentences. We just nod and smile and go back to reading the paper.

What is the reason for this? My answer is that we live in separate houses in small family units. When we eat there aren't big groups of cousins around with eager ears, there aren't lots of children. And perhaps, to an extent, television has taken hold of our attention. Young people look less to their elders for wisdom and prefer to get it from other sources.

If you've read this far then you probably deserve some kind of letters after your name. Enter the competition!

Email Article

Email Article