'The Future of the Book'

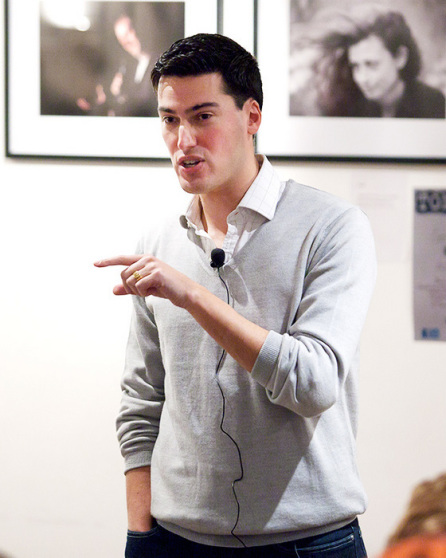

Michael Sissons: Past Chairman and MD of PFD literary and talent agency.

Lisa Gee: Writer and associate at the institute for the future of the book.

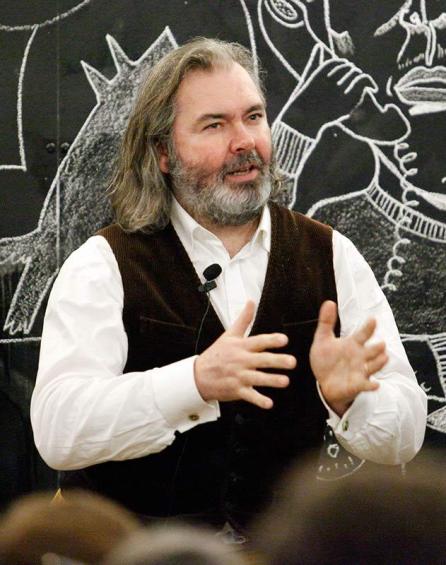

John Mitchinson: Co-founder of Unbound, man for all seasons.

The theme 'the future of the book' was suggested by our speaker Michael Sissons when I met him in the far reaches of Caithness. Before that - and before ToMax - I had gone for an interview with PFD Literary Agency for an internship. I knew that the lady interviewing me was head of the Television Department, but I was more interested in books. So I walked in and blurted out that I didn't watch TV.

'Oh, but our philosophy is that we are experts in all the media.'

'I understand that,' I said, desperate for any job paid or unpaid, whether it suited me or not, 'I think I could do that – see how ideas can be used in different ways. After all, we live in a society which is cross..umm...I mean, trans...ummm...'

'Multi-media?'

So that was that. Another reason they didn't want anything to do with me is that I displayed a complete ignorance of the book trade, conflating publishers and literary agents and book sellers.

I got to grips with it better ahead of our talk, so here is my brief and limited understanding for the benefit of the uninitiated. The ranks of self-publishing authors are growing now that they don't have to emulate Virginia Woolf and find a publishing house for the purpose. Now there is the internet. However, the (threatened) status quo is thus. Literary agents find writers and represent them. They fish for talent. Then, they offer ongoing advice to their clients (writers) about what to write and how to tailor their work for different media channels and markets. So, for example, they might advise a writer to transform his short stories into screenplays, soaps etc. for his own commercial good.

The next level is that literary agents approach publishers, who trust good agents more than bad ones to spot marketable talent. The authors expect their agents to negotiate them good contracts with the publishers. (Publishers used to deal with authors directly, but this part was wrestled away from them in the seventies). If the publisher thinks a book is a runner, they buy the rights. At this point, the offered book is probably incomplete: there is, perhaps, a synopsis, a few chapters and the writer's reputation. Publishers then help edit, manufacture and market the book. For the marketing process, they go about persuading booksellers like Waterstone's to buy the book in a rough form. These negotiations with the end sellers influence the editing of the book as the author completes it, and also the manufacturing – the cover, the paper, the lay-out. Boring part over.

John Mitchinson, the head of research for the QI Show, did not disappoint with his gleeful trivia, the accumulation of which he accredits to 'an ecclectic life [...] I have the habit of getting bored very quickly'. Yet the facts he deployed were not Quite Interesting red-herrings; instead, he skilfully harnessed everything into a single thread about the book industry - a persuasive endorsement of his latest venture Unbound, a company formed to dispell the stagnancy which our three speakers agreed afflicts traditional publishing houses.

The consensus among our speakers was not doom and gloom. Mitchinson stressed that the UK is entering a golden age for literature. He gave us the facts: more books (of all formats) are sold than ever, more people read and there are one hundred and fifty literary festivals every year in Britain. We have a burgeoning literary culture. However, the book is held prisoner by the tyranny of out-moded publishing. Although everything should be rosy for the book, the trade is awash with negativity. Publishers are perpetually saying 'no' – they are risk-averse and, for complex reasons to do with the advent of e-books, are not making any money.

People are ready to pay more for books, said Mitchinson. There are intelligent discerning markets. The problem is that publishers can't cater to the wants of those markets. As in the 1970s, when sportsmen's biographies seemed to preponderate on the high street, the book trade pushes publishers towards backing safe, populist bets - books 'with Jamie Oliver on the cover', as Michael Sissons put it. 'Take, for example, Philip Pulman' - back to Mitchinson - 'an author with a real following. The people buying his books are prepared to pay more for them. But – paradoxically - the book trade doesn't allow them to'.

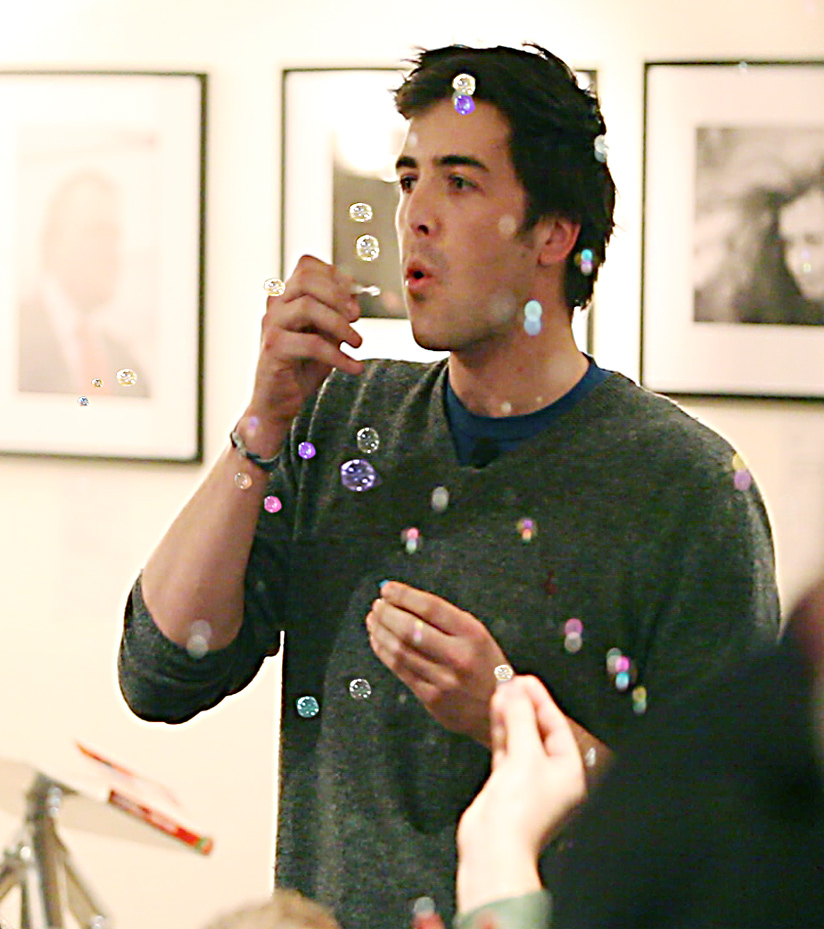

Michael Sissons with the crowd

Michael Sissons with the crowd

The idea of Unbound is to reach those markets. 'Authors, fundamentally, want to be read. So we are putting authors face to face with their readers.' Authors publish a pitch on the website. Readers visiting the site can then pledge to buy the book if it is made, which only happens when there are enough buyers to make the book viable. The book is a traditional physical object. The contributors's names are printed in the back. Simple and ingenious. Some traditional publishers at the evening defended their role to me after the talks. Authors do strive to be read, they said, but don't want a great deal to do with their audience. They also questioned whether readers really wanted to be involved at such early stage in a book's development. Often they want to buy a book produced by a trusted publishing house which has overseen the object's creation. Time will tell how much people's behaviour will change. Unbound is going well and they have forty titles to be released this year.

Lisa Gee, our speaker from the future of the book institute and our chosen ambassador for digital technologies called the shifts in the trade 'the biggest change since Guttenberg'. She said she was excited about digital media because of

-

What you can make

-

How you can reach people

-

Because of the new forms of business that are coming through

Lisa's talk was largely about point one. She challenged the audience's notion of a book, preferring to define it as something 'bounded'. Yet a book needn't have a single path running through it - it needn't be linear. Lisa herself is writing a biography of a failed poet at the end of the 19thC, and she wants the reading experience to reflect what it would be like to know him in real life. A real person's impression would be haphazard, quite unlike the birth-death progression of many biographies. New media allows the reader to follow skeins which interest them. Part of the excitement is, of course, the integration of different media. You can hear the voices of haunted women in Christine Wilkes' Underbelly or animations of the planets in The Solar System e-book published by Fabers. In Penguin's e-version of Jane Eyre, you can e-chat with other readers on the same page.

Lisa argued that poetry could be made viable again, now that the end reader could buy poems one at a time which is proving more popular. Poetry is heavy with allusion and so quick reference functions work well too.

Michael Sissons was the grandee among our speakers and lived up to it, holding the audience with a whisper at times, drawing on an illustrious career spent with the book. Afterwards, I overheard someone at the bar: 'Well, he nailed it, didn't he?'

Michael Sissons was the grandee among our speakers and lived up to it, holding the audience with a whisper at times, drawing on an illustrious career spent with the book. Afterwards, I overheard someone at the bar: 'Well, he nailed it, didn't he?'

Sissons spoke of the impossibility of making predictions. 'I visited the head of one of the largest publishers recently. “Paperbacks.” he said “That's the future we reckon, we're giving up hardbacks completely.” Then, that same week, I went to see the head of another, also very big, very prominent publisher – I can't tell you which – “We think” he said “that the paperback has had its day. People want books as luxury items.”. And there you have it. Two very erudite men, heads of vast organisations, in total disagreement.'

Sissons spent his entire career as an agent at one company, and it was his belief that things were going multi-media which led to the creation of PFD, a merger of a literary agency with an agency for talent.

His most revealing vignette, however, was from his experience as a customer. He recounted his attempt to buy a book about the Rugby World Cup for his godson at WHSmith. They didn't have it and he ordered it in for £20. A week later it still hadn't arrived. Ten days...no luck; two weeks...still no book.

'Well, sir, we haven't got that book in yet. You can have your money back.'

'No, I don't want my money back' Sissons growled, clearly infuriated to even think about the episode 'I want...a book...for my Godson!'

Eventually he gave up and went to Amazon.

“And in 36 hours that bloody book was with me. And it cost me fourteen quid! I hate telling that story, but in a funny way that says it all!”

John Mitchinson with the crowd

John Mitchinson with the crowd

Sissons was clear on one thing. A book is content. And he agreed with Mitchinson that the publishing world has become stale and hostile to many good books. Yet he was sceptical that an outfit like Amazon, who are effectively a bookseller, would be any good at publishing books, as they may look to do. 'Why should I trust them to produce a good book – to pick and produce it?' Perhaps this is the reason why James Daunt thinks the Kindle can be outdone (he has talked of the Waterstone's version – 'The Windle'). Amazon are a retailer and their product is made with a view to being a sales avenue; it could be more user-led.

Sissons ended as theatrically as he began, dwelling on the uncertainties:

“And that's where we are at the moment. And who knows where it's all going [and, with a wave, in a kindly whisper] but I won't be around to see it!”

Email Article

Email Article